Digital Technology and the Resurrection of Trust

A report from the House of Lords

By Stéphane Goldstein and Jane Secker

“A country’s education system needs to prepare its people for their role as citizens. In the digital world, this means they need to be empowered to be critical, digitally literate consumers of information.”

“A country’s education system needs to prepare its people for their role as citizens. In the digital world, this means they need to be empowered to be critical, digitally literate consumers of information.”

These couple of lines read like an extract from any self-respecting definition of information literacy. In fact, they come from ‘Digital Technology and the Resurrection of Trust’, the June 2020 report from the House of Lords Select Committee on Democracy and Digital Technologies. They form the opening statement of a chapter on active digital citizens, which stresses the crucial importance of information literacy (or, as the report terms it, critical digital media literacy) to a healthy, inclusive democracy. This resonated with us both immediately as the relationship between information literacy and citizenship was something highlighted when revising the CILIP definition of IL in 2018. The chapter is just one part of a document that roams widely in an analysis of the relationship between citizenship and online discourse, but it addresses the absolute need for the education system to catch up with the implications of democracy in the digital age.

The report, and the parliamentary inquiry and evidence-gathering that preceded it, is the latest example of how the public discourse in the UK has evolved in recent times in its understanding of the importance and relevance of information literacy. Only five years ago, another House of Lords report, on the UK’s digital future, singularly failed to see digital literacy in terms other than functional skills, closely aligned to ICT and know-how associated with the use of computer technology. Even in 2017, the skills component of the Government’s Digital Strategy was focused largely on basic skills, digital exclusion and the needs of the economy, with little or no reference to critical thinking and citizenship. But with growing concerns about disinformation, online harm, malpractice on social media platforms and subversion of democratic processes by unfriendly non-UK players, attitudes from public agencies began to shift. In 2018, the House of Commons DCMS Committee interim report on disinformation recognised the relationship between digital literacy and making informed choices about material encountered online; and it recommended that digital literacy should be the fourth pillar of education, alongside reading, writing and maths. In 2019, the Cairncross Review on a sustainable future for journalism stated that critical media literacy is necessary to help people judge the quality of online news, and recommended that the Government develops a media literacy strategy. That recommendation was taken up in the Online Harms White paper, published later this year; as far as we know, the Government remains committed to setting out this strategy before the end of 2020. And now, this latest House of Lords report builds on these various initiatives.

Progress by public agencies towards developing policies and practice on information literacy (and associated literacies) has certainly been slower in the UK than in other countries. But the Lords report makes up for some of the lost time by being quite hard-hitting in its policy prescriptions. For starters, its definition of digital media literacy is inclusive and closely aligns with how we view information literacy:

“We use the term ‘digital media literacy’ because our purposes go beyond, but do include, the functional skills required to use technology. We define digital media literacy as being able to distinguish fact from fiction, including misinformation, understand how digital platforms work, as well as how to exercise one’s voice and influence decision makers in a digital context.”

It goes on to note that too often, digital media literacy is confused with computer science; and that it is not enough to be merely a technically proficient consumer of digital technologies. And it laments that the Government does not have a full understanding of the critical ways in which digital media literacy and technical computing skills differ. But the report is particularly damming about the perceived shortcomings of the education system and of the school curriculum. For instance:

“The Government’s focus on computing education is insufficient; basic digital skills are not enough to create savvy citizens for the digital era. The Department of Education would appear to be struggling to anticipate the implications of the technological challenges of the 21st century.”

And, taking a dim view of the Department for Education’s current approach, it goes on to suggest that the Department demonstrates a lack of understanding about what is needed to bring about necessary change; and that it struggles to anticipate the implications of technological challenges of the 21st century.

How might these shortcomings be addressed? The report makes two important recommendations, which we quote in full:

“The Department for Education should review the school curriculum to ensure that pupils are equipped with all the skills needed in a modern digital world. Critical digital media literacy should be embedded across the wider curriculum based on the lessons learned from the review of initiatives recommended above. All teachers will need support through CPD to achieve this.”

And, to develop the evidence base in a thorough and comprehensive manner:

“Ofsted, in partnership with the Department for Education, Ofcom, the ICO and subject associations, should commission a large-scale programme of evaluation of digital media literacy initiatives.”

It is gratifying that a distinguished parliamentary committee has reached such conclusions. Two of its members are former education ministers, which adds weight to its findings: Baroness Morris, who as Estelle Morris was Secretary of State for Education in 2001-02; and Lord Knight, who as Jim Knight was Minister of State (Education and Skills, Schools and 14-19 Learners) in 2006-07. Of course, reports from parliamentary committees do not make Government policy, and as things stand, the Government has not yet formally responded to this particular report. Indeed, it is not impossible that they may reject its recommendations, in the same way that it rejected the House of Commons DCMS Committee’s 2018 proposal to make digital literacy the fourth pillar of education.

All the same, we hope that the report will make an important contribution to current thinking on making the school education system more fit for purpose. For our part, a small group of us have launched an initiative that supports a greater integration of information literacy – and associated concepts, such as media literacy, digital literacy, news literacy and critical literacy – into the school curriculum. The initiative takes the form of a statement which we are asking interested parties to sign (this was actually made public before the publication of the Lords report, but it shares the same concerns). The aim is to get as wide a variety of individuals and organisations as possible to lend their names with a view to influencing public policy in this direction. Please consider signing this here if you agree with what both we and the Lords Committee are saying. Destiny is all!

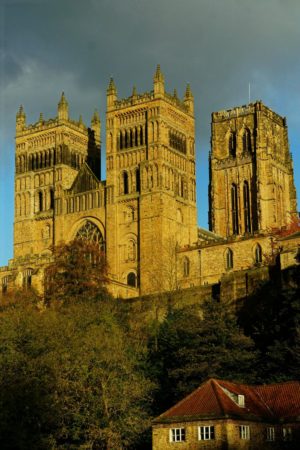

Authors’ note: ‘Destiny is all’ is a tongue-in-cheek reference to our mutual appreciation of ‘The Lost Kingdom’, a BBC-Netflix series based on the books by Bernard Cornwall and set in the 9th and 10th centuries, in Anglo-Saxon and Danish England. Like all good historians, we recognise the need critically to assess your sources, but we heartily recommend this series if you are looking for a lockdown box set to whet your appetite for researching the true historical characters on which much of the series is based! The city of Durham features in several episodes of the series – hence the photo of its magnificent cathedral.

![InformAll [logo]](https://www.informall.org.uk/wp-content/themes/informall/assets/img/informall-logo.svg)